MS 4.3.2-Gesichter/C01721_2025

Gespeichert von theresa.sturm am Do, 03/07/2025 - 10:14MS 4.3.2-Gesichter/C01721_2025

Gespeichert von sarah.roller am Di, 01/07/2025 - 15:10

Mo, 14. Juli 2025 —— 19:30 - 21:00

Utopie und Aufbruch der 1968er – Was von politischer Rebellion und individueller Selbstbefreiung geblieben ist

Rainer Langhans (Autor und Filmemacher)

Christa Ritter (Journalistin und Filmemacherin)

Prof. Dr. Martin Saar (Goethe-Universität, Normative Ordnungen)

Moderation: Rebecca C. Schmidt (Goethe-Universität, Normative Ordnungen)

Begrüßung: Dr. Doreen Mölders (Direktion des Historischen Museums Frankfurt)

Die sogenannten „68er“ waren nicht nur eine politische Gegenbewegung zu autoritären Strukturen, überkommenen Normen und dem als verkrustet empfundenen Nachkriegsdeutschland, sondern auch Zeitpunkt eines spirituellen Aufbruchs. In neu entstandenen Gemeinschaften wie beispielsweise der „Kommune I“ suchten viele nach neuen Formen der Liebe, des Zusammenlebens und der Solidarität. Materieller Besitz wurde hinterfragt, emotionale Offenheit und geistige Freiheit neu entdeckt. Die Bewegung galt als ein Versuch, sich aus dem Schatten des Faschismus zu lösen und stattdessen eine Welt aufzubauen, die auf Gleichheit, individueller Freiheit und Selbstbestimmung basiert.

Die Diskussionsrunde mit Rainer Langhans, Christa Ritter, die seit 1978 zur Selbsterfahrungsgruppe um Langhans gehört, und dem Sozialphilosophen Martin Saar widmet sich diesen utopischen Vorstellungen, die von der 1968er Bewegung ausgingen, und beleuchtet deren Ideale, Impulse, individuelle und gesellschaftspolitische Nachwirkungen. Im Fokus stehen die visionären Vorstellungen einer gerechten, freien und demokratischen Gesellschaft, die die patriarchalen Machtverhältnisse aufzulösen suchte. Dabei wird auch der Wandel utopischen Denkens im Laufe der Jahrzehnte thematisiert: Inwiefern ist die 68er-Utopie heute noch anschlussfähig? Welche Elemente haben sich im kollektiven Gedächtnis verankert – und welche sind gescheitert oder in Vergessenheit geraten? Und welche Rolle spielen individuelle Freiheit und Selbstbestimmung heute?

In einer Zeit multipler Krisen gewinnt die kritische Auseinandersetzung mit früheren gesellschaftlichen Entwürfen neue Relevanz – auch um aktuelle emanzipatorische Bewegungen besser zu verstehen und weiterzudenken. Die Veranstaltung lädt daher dazu ein, die 68er nicht nur als historisches Phänomen zu betrachten, sondern als Ausgangspunkt für die Frage nach heutigen Utopien.

Die Veranstaltung ist öffentlich. Der Eintritt ist frei

Die Tabelle stellt eine Monatsübersicht über den jeweiligen Monat dar. Die Spalten sind nach Wochentagen aufgeteilt. Die Tage, an denen Veranstaltungen stattfinden, sind verlinkt.

| Mo | Di | Mi | Do | Fr | Sa | So |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

06 |

|

08 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

21 |

22 |

|

|

|

|

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

|

|

Mi, 09. Juli 2025 —— 19:00

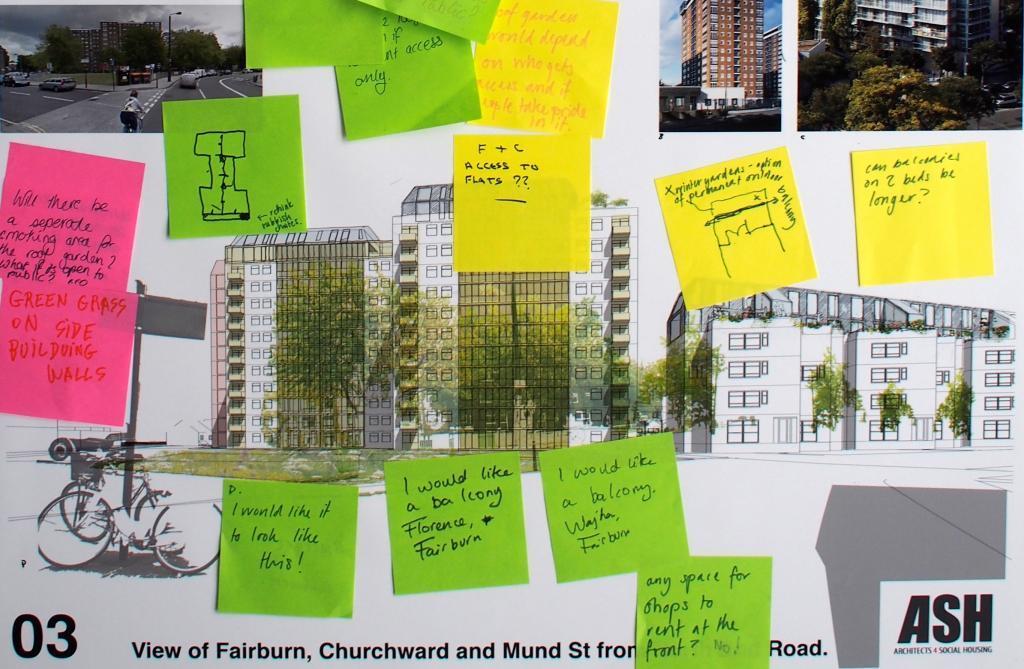

Architects for Social Housing. Architecture, Community and Research against the Housing Crisis

Ein Abend mit Geraldine Dening, Mitgründerin von Architects for Social Housing (ASH)

Moderation: Tabea Latocha

Das 2015 gegründete Londoner Kollektiv Architects for Social Housing (ASH) setzt sich mit seiner Architekturpraxis für eine soziale, demokratische und gemeinwohlorientierte Stadtentwicklung und Wohnungspolitik ein. Dem Prinzip „for socialism in architecture“ verpflichtet entwickeln die Architekt*innen von ASH in Kollaboration mit Bewohner*innen von Sozialwohnungen in London Antworten auf die gravierende Wohnungskrise. Um die Privatisierung und den Abriss von bezahlbarem Wohnraum zu verhindern, entwirft ASH konkrete planerische und architektonische Alternativen für eine sozial-ökologische Weiterentwicklung von council housing estates.

In ihrem Vortrag gibt Geraldine Dening einen Einblick in die Arbeitsweise von ASH, stellt konkrete Projekte des Kollektivs vor und diskutiert, wie Architektur- und Planungspraxis als Instrumente für eine sozial-ökologische Transformation genutzt werden können. Dabei geht sie auf die Herausforderungen und Potentiale ein, die mit kollaborativer Architekturpraxis und dem bestandserhaltenden Retrofitting von Sozialwohnsiedlungen verbunden sind.

Im Anschluss an den Vortrag kommentiert Prof. Maren Harnack von der FRA UAS den Input und stellt eine Verbindung zur Situation in Frankfurt am Main her – einer Stadt, die ebenso stark unter dem Druck des Wohnungsmarktes leidet wie London und vor ähnlichen Fragen einer sozial und ökologisch gerechten Stadtentwicklung steht.

Eine Kooperation mit dem Graduiertenkolleg Gewohnter Wandel und dem Deutschen Architekturmuseum (DAM).

Die Veranstaltung findet auf Englisch statt / The event will be held in English.

Es werden 2 Fortbildungspunkte der Architekten- und Stadtplanerkammer Hessen (AKH) vergeben.

Vortrag und Diskussion

Ort: Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM)

Eintritt: 7 €

Die Tabelle stellt eine Monatsübersicht über den jeweiligen Monat dar. Die Spalten sind nach Wochentagen aufgeteilt. Die Tage, an denen Veranstaltungen stattfinden, sind verlinkt.

| Mo | Di | Mi | Do | Fr | Sa | So |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

06 |

|

08 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

21 |

22 |

|

|

|

|

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

|

|

Sa, 23. August 2025 —— 17:00 - 23:00

Rooftopday im HMF

Das Historische Museum zeigt die beiden ältesten Rooftops der Stadt:

1.) Das „Belvederchen“ im Haus zur Goldenen Waage in der Neuen Altstadt: eine Dachterrasse mit Zierbrunnen, Laube und Blick auf den Domturm. Zugang über das Treppenhaus des Stoltzemuseums

2.) Exklusiv für den Rooftopday öffnet das Museum auch den Dachstuhl des mittelalterlichen Rententurms im HMF mit einem spektakulären Ausblick auf den Main. Vom Foyer können sich die Gäste ein Getränk mit nach oben nehmen und die Aussicht genießen.

Besucher*innen sollten mit Wartezeiten rechnen: die Plattform des Rententurms ist für maximal 15 Personen auf einmal zugänglich, im Belvederchen können sich jeweils bis zu 20 Personen aufhalten.

Eine Anmeldung ist nicht erforderlich.

Für Fragen und Informationen zum Museum, zum Belvederchen und dem Rententurm stehen die Freunde und Förderer des HMF bereit.

Der Rooftopday ist auch der SaTourday mit freiem Eintritt in alle Frankfurter Museen. Nutzen Sie also gerne die Gelegenheit, das Historische Museum und sein Programm kennenzulernen.

Samstag, 23. August 2025 von 17 bis 23 Uhr

Eintritt frei

Mit freundlicher Unterstützung durch die Freunde & Förderer des Historischen Museums.

Die Tabelle stellt eine Monatsübersicht über den jeweiligen Monat dar. Die Spalten sind nach Wochentagen aufgeteilt. Die Tage, an denen Veranstaltungen stattfinden, sind verlinkt.

| Mo | Di | Mi | Do | Fr | Sa | So |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

06 |

|

08 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

21 |

22 |

|

|

|

|

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

|

|

Ausstellungshaus, Ebene 0

Globale Ereignisse im Spiegel Frankfurter Finanzobjekte

Der Zusammenhang lokaler Ereignisse mit globalen mPhänomenen zeigt sich durch Frankfurter Sammlungsobjekte: So erzählt eine Kreditkarte etwas über die Ökobewegung der 1970er Jahre, eine Aktie zeigt uns die Zusammenhänge kolonialer Märkte des 19. Jahrhunderts oder eine Medaille die weltweiten Folgen eines indonesischen Vulkanausbruchs. Koloniale Expansion, Krieg, Migration oder Klimakatastrophen fließen in die Betrachtungen ebenso ein wie technologische Innovationen und kultureller Wandel. Der Plural „GlobalisierungEN“ ist dabei bewusst gewählt – denn die Geschichte verläuft nicht einheitlich, sondern in überlappenden Bewegungen. Mit einem Schwerpunkt auf der Frankfurter Sammlung numismatischer Objekte nutzt die Ausstellung das Potenzial materieller Kultur für die historische Vermittlung. Der bewusste Perspektivwechsel – vom Objekt zum globalen Zusammenhang und zurück – ermöglicht unerwartete Einsichten in wirtschaftliche, politische und gesellschaftliche Entwicklungen.

Am Beispiel einer Frankfurter Teuerungsmedaille aus dem Jahr 1817 lässt sich der Reiz der Ausstellung gut verdeutlichen: Auf der Rückseite der Medaille ist vermerkt, wie teuer die Preise für Getreide und andere Lebensmittel waren. So weit, so unverdächtig. Hintergrund zu diesem Jahr des Hungers 1817 war allerdings ein Vulkanausbruch auf Indonesien zwei Jahre zuvor. Die enorme Aschewolke, die der Vulkan ausstieß, verdeckte die Nordhalbkugel langfristig, sorgte für nasse Bedingungen und zerstörte 1816 durch vermehrte Unwetter großflächig die Ernten.

Viele Mythen, aber auch handfeste Theorien ranken sich um dieses historische Weltereignis und werden mit ihm in Zusammenhang gebracht. So könnte es sein, dass aufgrund des zerstörten Getreides mehr Pferde geschlachtet wurden, was die Durchsetzung des Fahrrads beschleunigte. Möglicherweise lässt sich auch die Geburt Frankensteins auf das globale Wetterereignis zurückführen, denn Mary Shelley war während einer Reise in die Schweiz wegen der nassen Wetterbedingungen dazu gezwungen viel Zeit drinnen zu verbringen. Zum Zeitvertreib schrieb sie Horrorgeschichten, darunter Frankenstein. Auch die dramatischen Sonnenuntergänge in den Bildern der Biedermeier-Zeit lassen sich vielleicht auf die Aschepartikel des Vulkanausbruchs, die noch Jahrzehnte in der Umluft blieben, zurückführen.

Diese und weitere Zusammenhänge lassen sich durch einen tiefen Blick in die Objekte entdecken und offenbaren die Verflechtungen der Welt – auch schon weit vor einer Zeit, die wir heute als „Globalisierung“ verstehen. “Die Welt im Geld“ verbindet auf den ersten Blick vielleicht unscheinbare Objekte mit spannenden Kontexten, Geschichte mit Gegenwart – und Frankfurt mit der Welt. Eine Einladung zum Staunen, Hinterfragen und Neudenken.

Kuratorinnen:

Christina Bach, Yi Liu

Kuratorische Assistenz:

Melda Demir, Bennet Keller

Fördererung:

Frankfurter Sparkasse

Stabstelle Inklusion

Kooperationen:

Goethe Universität Frankfurt

Deutsche Bundesbank

Historisches Archiv der Commerzbank